2024.58

It's ludicrous to posit, for an infinitesimal unit of time, that poetry followed me from a previous life or that there's prior art for why I'm so comfortable with Death.

When I was in my undergrad at Missouri State University, and was working on my first "poetry portfolio" which I needed to turn in at the end of the semester, I took my poems up to the Writing Center—which is how one got feedback on things they were writing in those days—and I met a grad student named Dale.

Outside of the class I was taking, Dale was the first poet I showed my work to. He had a lot of kind words for my first batch of poems, (which were not great), and we became friends. Unlike me, Dale loved the Ozarks. He liked to talk about fishing and wrote poems about fishing and his accent was more "country" than mine. Strange bedfellows—us. Back then, I was too busy acting like I was from somewhere else, a very childish thing to do, wanting to be from anywhere but the Ozarks. Such an idea never crossed Dale's mind for even an instant and I'm thankful, after all these years, we're still friends.

I say all this because Dale introduced me to the work of Frank Stanford.

Frank Stanford, in case you've never heard of him, may have been the best American poet to ever come out of the Ozarks. And if I must be pedantic about what "from" means, it's true that while Stanford was born in Mississippi—he moved to Arkansas at the age of twelve—and in my book, that's young enough for the Ozarks to get its hooks into you. And I firmly believe if you read his work, it's hard to argue he was from anywhere else.

Stanford published seven collections between the ages of 22 and 29, including the epic poem The Battlefield Where The Moon Says I Love You, a book I still salivate over owning someday—especially a first edition—from time to time. He lived in Arkansas and Southwest Missouri. He worked as a land surveyor. He wrote constantly. One of my professors in college was, at one time, an acquaintance of his.

And the more I learn about him, the more I can't understand how he was so prolific or so naturally talented. It's hard to imagine we never walked the earth at the same time, Stanford having died in June of 1978, seven months before I was born.

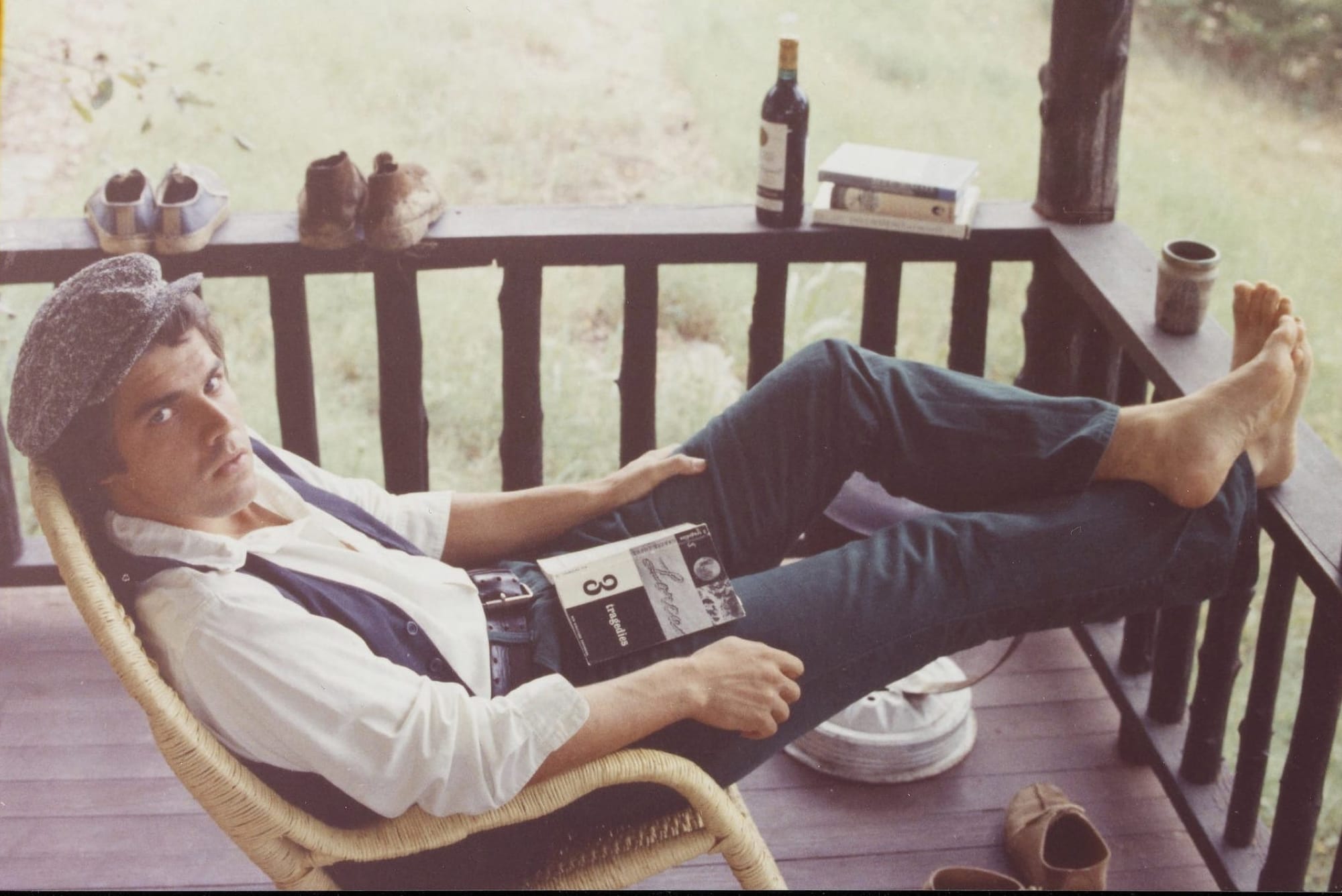

He was a poet who wrote about Death like I write about Death, except he didn't hide his excessive amount of poems where Death was a character or subject, nor did he change his poems to be about something other than Death. In another lifetime, where I might be brave or talented enough, I might've written something like The Last Supper. I could've been satisfied with a humble porch in Arkansas and reading books in the hot afternoon and maybe even think about starting a small press.

But then again, I don't want to shoot myself in the chest three times. At least, not anymore.

Today's Poem

It's wishful thinking to believe, for even a moment, in some other life I was Frank Stanford. That I shot myself in the chest and seven months later, found myself born again on Earth, to another family in the Ozarks, where I would grow up broken-hearted. It's ludicrous to posit, for an infinitesimal unit of time, that poetry followed me from a previous life or that there's prior art for why I'm so comfortable with Death. That this life is merely a continuation of a previous life— but in this life, things changed just enough for me to make different decisions.

Just utter foolishness, some might say.