2024.56

Somehow I keep thinking I've written all the poems I need to about my father. This one didn't exactly come from nowhere but let's just say I wasn't expecting it.

Poetry called to me when I was eleven like it was the Holy Spirit. I woke up one morning, maybe after reading Robert Frost, with a strange idea to write my very own poem—like it came to me in a dream and I simply woke to a sudden new desire in my heart. End of story.

Hallowell, Kansas, 1990. I wrote by hand on loose paper bound in a 3-ring binder. If I messed up a word or wanted a different line, (which happened often), I'd start over and copy everything I'd written—up to the point I fucked up—on a new piece of paper. This could happen multiple times with every poem I wrote. And I wrote hundreds.

What I didn't know was the why. Why did I want to write?

In hindsight, I was going through trauma. I didn't realize it the time, of course. Poetry, for me, started as a means of survival. I was processing pain I had no other outlet for. I used metaphor to hide secrets. Images to disguise hurt.

When I was 19, I took my first poetry class with Marcus Cafagña at Missouri State. It was Southwest Missouri State back then, a regional school, and I enrolled because I simply wanted to know if anyone else might believe I could write worth a shit.

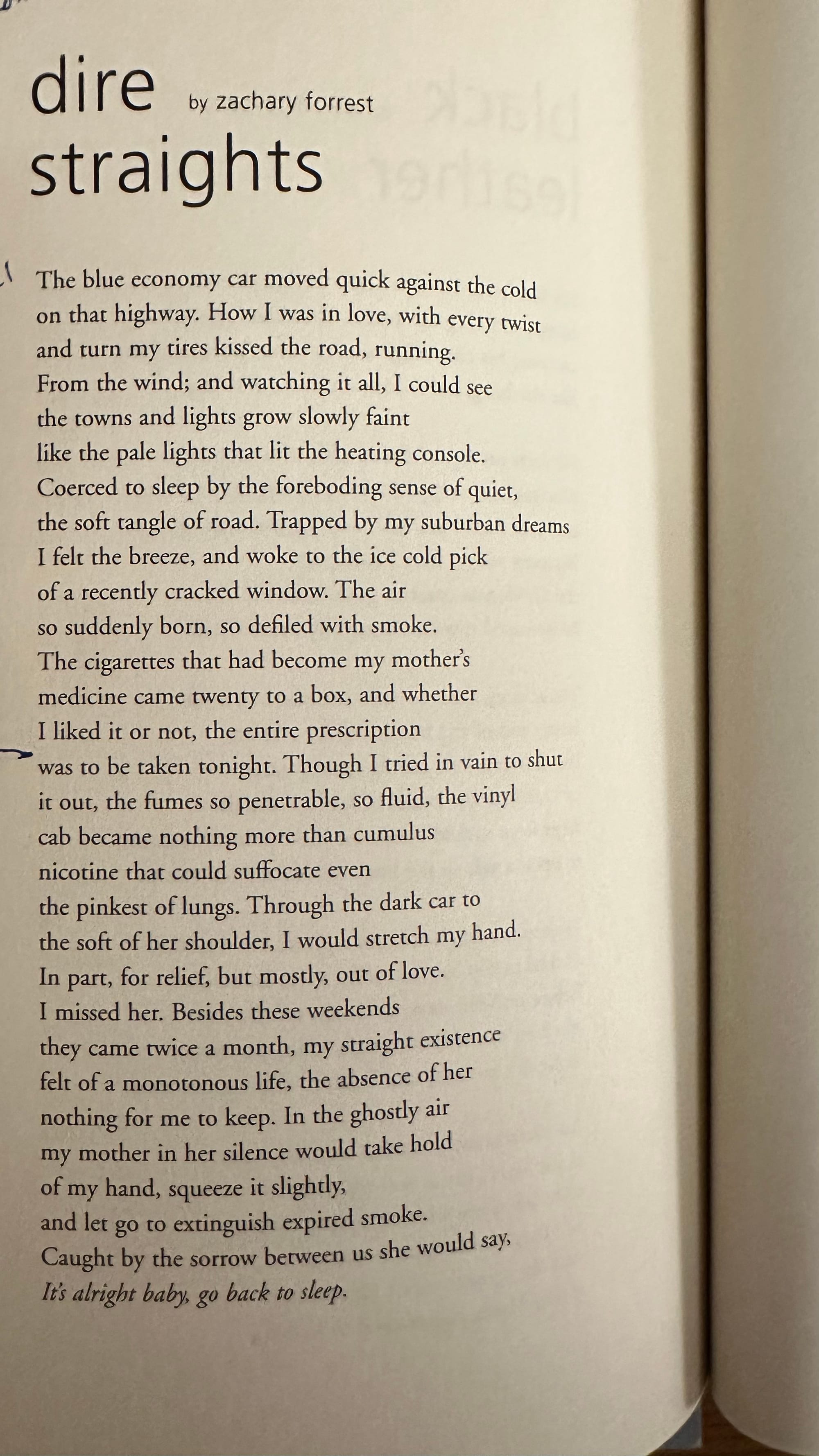

Marcus taught me the technicalities of a good poem. I learned more in that first class about how choices are made with poetic devices and why you might make one choice over the other. And I was ecstatic. I understood constraints. The first poem I wrote for Marcus was called Dire Straights. It was published in the Moon City Review back when it was just a regional journal with content from students. I couldn't wait to be the next Billy Collins.

I write poetry for one simple reason, and that is—in the words of Kurt Vonnegut:

...to experience becoming, to find out what's inside you, to make your

soul grow.

Poetry isn't meant to be anything else or more than. I used to think it could be the thing that made my living, but those days were already over in 1999, and I couldn't be more thankful that poetry isn't tied to money for me. I don't want poetry to be my means of living. I just want it to make my soul grow. In the words of the poet Matthew Zapruder:

In the end, poetry cannot be a career. Nor can it be a platform, or a brand. Those things may get you someplace in the short term, like to money or jobs or a little bit of poetry fame (another oxymoron). Of course almost all of us need money and jobs, so I would never criticize anyone who is trying to get those things (within ethical bounds of course). But if that is the goal, it will not be satisfying. It’s not enough. The only solution is to give up on getting anything for your writing, and to push everything as far as you can, in whatever direction you feel deep inside your (yes) soul really, truly matters. If you are doing that, you will be ok, whether you are a professor or a baker.

Poetry's real value is to make your soul grow. So naturally, I thought every poet knew this, and up until recently, I really believed something unhinged—that success in poetry must mean your soul is gargantuan.

Dear Reader: this is not often the case.

Poets, like many artists, can be notoriously self-centered. Bukowski wasn't exactly known to have been a good person. The late Michael Burns, another poetry professor of mine, knew Frank Stanford (who was, arguably, a poetic genius) and those stories he told, about himself or Frank, weren't exactly great either. I've rarely heard a good narrative about Billy Collins from people who've met him—a former Poet Laureate of the United States. A giant in poetry. And while I won't repeat the stories I've heard here, because they're all third-hand, let's just say poetry doesn't seem to make his soul grow.